This post covers a new .NET 10 feature that lets you build and run a single C# file without creating a .csproj project file. We will demo it, outline its capabilities, note its limitations and suggest possible workarounds.

dotnet run app.cs

Let’s create a simple C# source file named app.cs. Its code relies on top level statement. This means that there is no Main() method nor Program class explicitly defined.

|

1 |

Console.WriteLine("Hello, world"); |

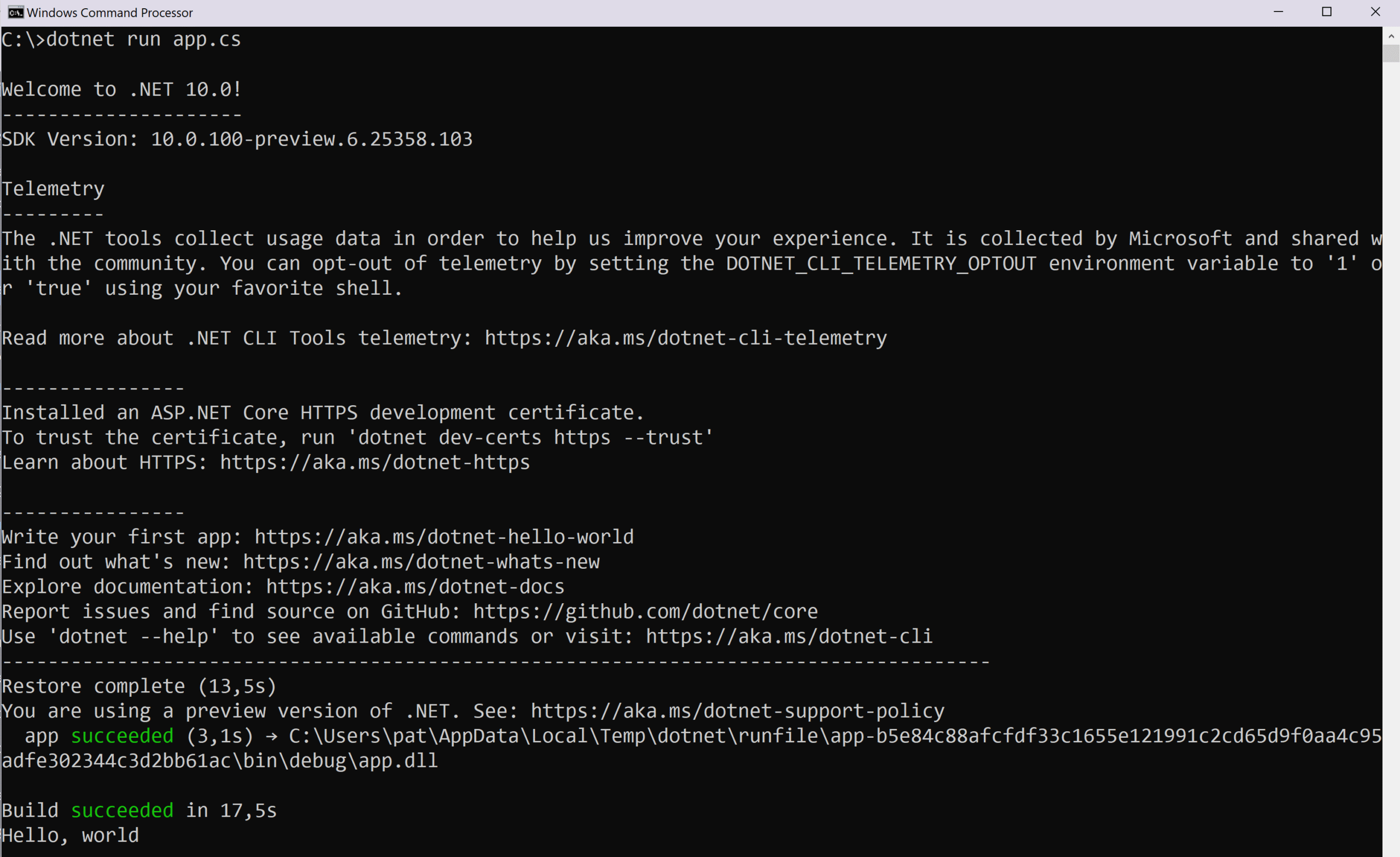

Now let’s open a command window in the directory containing the file app.cs. Just type:

|

1 |

dotnet run app.cs |

Et voilà! It takes 13 seconds to restore and compile and finally Hello, world gets printed.

We can see that a temporary directory gets created. It actually contains the app.dll executable file.

|

1 |

C:\Users\pat\AppData\Local\Temp\dotnet\runfile\app-b5e84c88afcfdf33c1655e121991c2cd65d9f0aa4c95adfe302344c3d2bb61ac\bin\debug |

If we modify app.cs and re-run dotnet run app.cs the same temporary directory gets re-used. This time it is much faster since no more restoring is required:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

C:\>dotnet run app.cs Restore complete (0,3s) You are using a preview version of .NET. See: https://aka.ms/dotnet-support-policy app succeeded (0,3s) → C:\Users\pat\AppData\Local\Temp\dotnet\runfile\app-b5e84c88afcfdf33c1655e121991c2cd65d9f0aa4c95adfe302344c3d2bb61ac\bin\debug\app.dll Build succeeded in 1,2s Hello, world2 |

Now, let’s explore the available features, which use new preprocessor directives—lines that begin with #:.

#:sdk to add SDK reference

With #:sdk we can import a .NET SDK. As a consequence it’s now possible to run a complete ASP.NET Minimal API from just one .cs file. Here’s an example:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

#:sdk Microsoft.NET.Sdk.Web using Microsoft.Extensions.Hosting; var app = WebApplication.Create(); app.MapGet("/", () => "Hello, world!"); app.Run(); |

Just run dotnet run app.cs then open http://localhost:5000 in your browser et voilà!

#:package to add Nuget package reference

One or several Nuget package reference can be added this way:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 |

#:package Newtonsoft.Json@13.0.3 using Newtonsoft.Json.Linq; string json = @"{ ""name"": ""Alice"", ""age"": 30 }"; var obj = JObject.Parse(json); string name = (string)obj["name"]; int age = (int)obj["age"]; Console.WriteLine($"{name} is {age} years old."); |

Wildcards can be used in version numbers, and the examples below also work. The wildcard resolves to the latest package version.

|

1 2 3 |

#:package Newtonsoft.Json@* #:package Newtonsoft.Json@13.* #:package Newtonsoft.Json@13.0.* |

The program below rely on the C# 14 extension everything feature. As long as .NET 10.0 is in preview it requires both #:property directives:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 |

#:property TargetFramework=net10.0 #:property LangVersion=preview var s = "this is a long string that needs to be truncated".AsSpan().Truncate(20); Console.WriteLine(s.ToString()); static class ExtensionMethods { // C# 14 syntax extension<T>(ReadOnlySpan<T> span) { public ReadOnlySpan<T> Truncate(int maxLength) { return span.Length <= maxLength ? span : span.Slice(0, maxLength); } } } |

The two #:property directives are equivalent in .csproj of:

|

1 2 |

<TargetFramework>net10.0</TargetFramework> <LangVersion>preview</LangVersion> |

#:project to reference a .csproj project file

It is possible to reference a project file through its relative or absolute file path:

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

#:project .\MyClassLibrary\MyClassLibrary\MyClassLibrary.csproj using MyClassLibrary; Class1.Method(); |

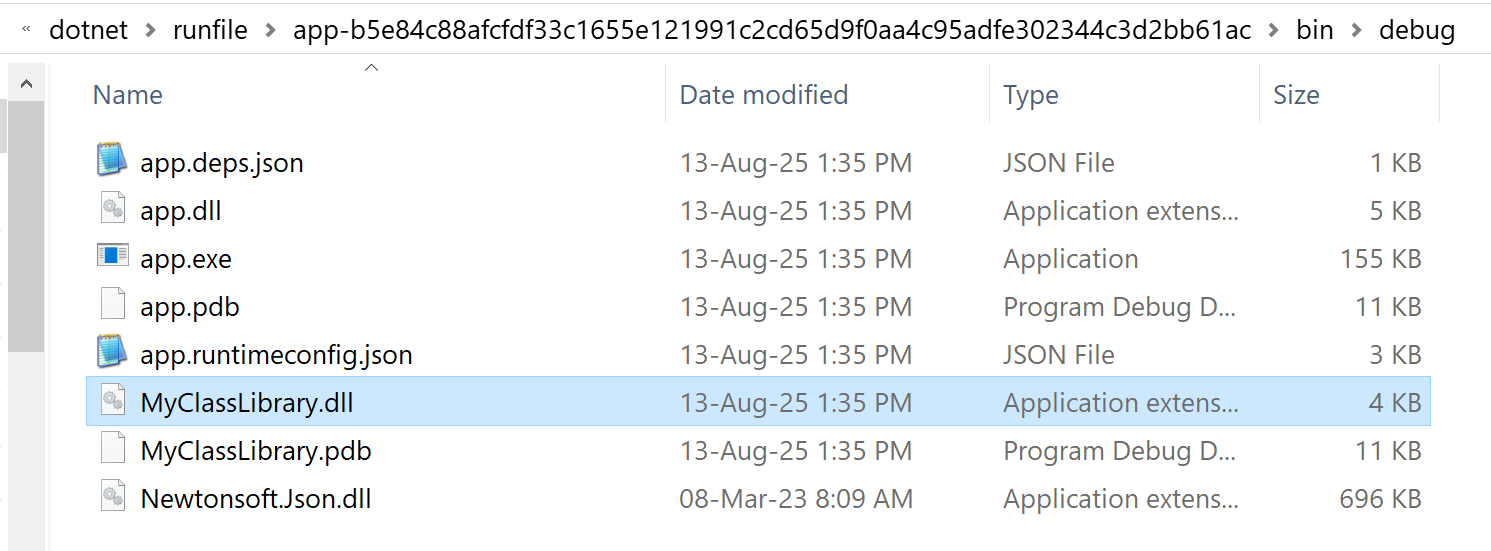

Notice that MyClassLibrary.dll and .pdb get copied to the temporary path. Also, Newtonsoft.Json.dll remains from a previous execution.

#!/usr/bin/dotnet run (Unix-like only)

|

1 2 3 |

#!/usr/bin/dotnet run // (Unix-like only) Console.WriteLine("Hello, world"); |

A script line beginning with #! is known as a shebang. On Unix-like systems, it tells the OS how to execute the file directly. Here, it specifies /usr/bin/dotnet run <file> as the command. Once you make the script executable with chmod +x app.cs, you can run it straight from the shell:

|

1 2 |

chmod +x app.cs ./app.cs |

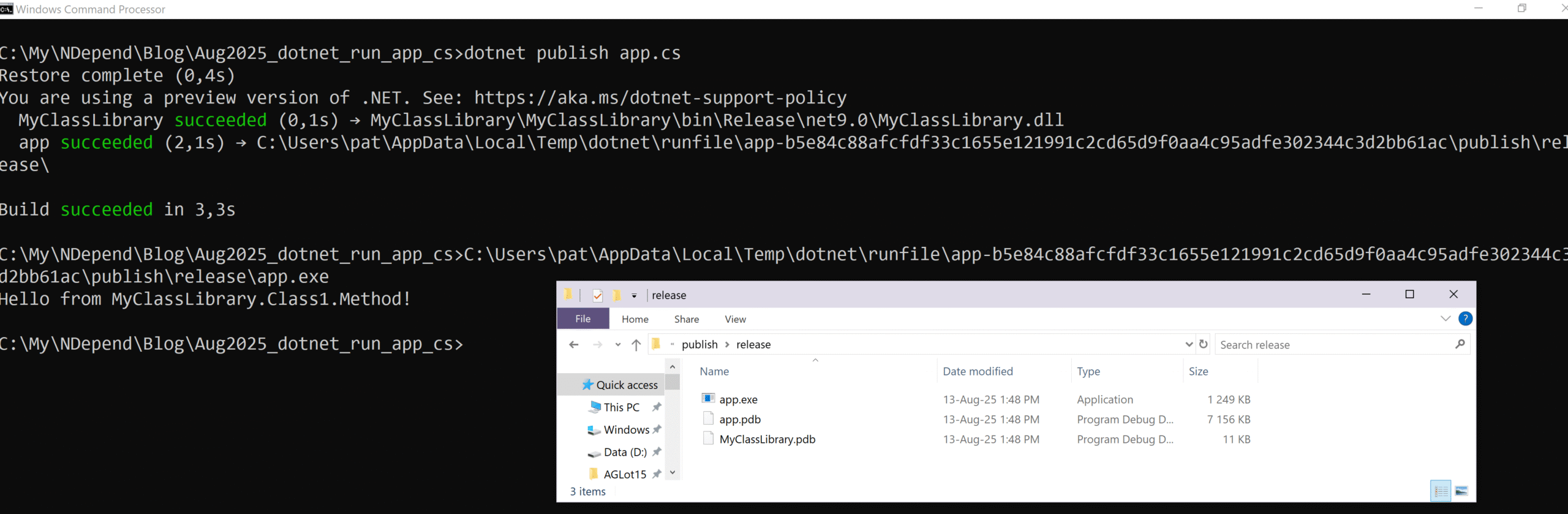

dotnet publish app.cs

It is possible to publish your file based application with this simple command: dotnet publish app.cs. The application gets published in the temporary folder C:\Users\pat\AppData\Local\Temp\dotnet\runfile\app-b5e84c88afcfdf33c1655e121991c2cd65d9f0aa4c95adfe302344c3d2bb61ac\publish\release:

Missing project file workaround with Directory.Build.props

You can work around some of the current directive limitations by using a Directory.Build.props file. For example we can rewrite the extension members sample by removing the #:property directives. The file app.cs content is:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 |

using System; var s = "this is a long string that needs to be truncated".AsSpan().Truncate(20); Console.WriteLine(s.ToString()); static class ExtensionMethods { // C# 14 syntax extension<T>(ReadOnlySpan<T> span) { public ReadOnlySpan<T> Truncate(int maxLength) { return span.Length <= maxLength ? span : span.Slice(0, maxLength); } } } |

Then create a file named Directory.Build.props in the same directory (or a parent directory) with this content:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

<Project> <PropertyGroup> <TargetFramework>net10.0</TargetFramework> <LangVersion>preview</LangVersion> </PropertyGroup> </Project> |

dotnet run app.cs now works because it takes account of Directory.Build.props. In fact under the hood a virtual project is built in memory through the Microsoft.DotNet.Cli.Commands.Run.VirtualProjectBuildingCommand.

When to use dotnet run app.cs?

- Beginner-friendly – The .NET team aims to simplify learning for newcomers. Like Node.js or Python, .NET now supports a smooth single-file experience.

- Prototyping – File-based program is ideal for quick and dirty prototypes.

- Scripts – Tasks that once required Bash or PowerShell can now be written just as easily in C#.

- Samples – Instead of creating a separate folder and project for each example, you can keep multiple sample apps in one folder, with each

.csfile acting as its own runnable example. In this scenario having a commonDirectory.Build.propsfile to factorize some properties makes even more sense.

Here’s a Reddit comment about this post that speaks for itself: (from EntroperZero)

“I was lukewarm on this until I found the perfect use case for it last night.

I was working on a project that doesn’t use .NET at all, and I just needed to convert some binary data from one format into another format. I wrote a 20-line convert.cs in about 5 minutes, and just ran it straight from the command line.

I didn’t have to set up a project, and it didn’t spit out a bin folder with a bunch of junk in it that I would have to add to .gitignore. The script can just live in the source tree for this project without adding any additional infrastructure. And I can write like 5 more of these that I’ll need for other formats.”

dotnet project convert app.cs

Eventually, you may want to convert your single-file program into a full project that requires a .csproj file.

Running the command dotnet project convert app.cs sets up a project file automatically: it makes a folder for your file, adds a .csproj, remove #:directives in app.cs, and turns these directives into proper MSBuild settings and references.

Conclusion

File-based program is not the first technology that let’s .NET developers run C# code without a project file. For years, the projects CS-Script, dotnet-script, Cake or even LinqPad have enabled scripting, REPLs (Read-Eval-Print Loop), and other lightweight ways to run C# without a full project. Thanks to the new dotnet run app.cs built-in support, developers can start coding right away—no extra setup, installation, or configuration needed.

.NET 10 will supports single file-based program but multiple files-based program is on its way for .NET 11. “We’re moving support for multi-file out to .NET 11 so we can focus on making the single-file experience great in .NET 10.”

As of August 2025, this feature is still in preview. This post will be updated as it progresses toward general availability with .NET 10 in November 2025.

I can’t think of much that is more useless than this feature.

C# code could be run independently, without a .csproj to compile, years ago. But that use case is rare and restrictive, for safety and support reasons.

If you have something you want to compile via command line (e.g. automated build in some third-party deployment) then do it right with a project, or don’t do it at all.