C# 14 introduces extension members — also known as extension everything.

The New C# 14 Extension Method Syntax

The example below demonstrates how to migrate a traditional extension method using the this keyword to the new extension member syntax.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 |

var s = "this is a long string that needs to be truncated".AsSpan().Truncate(20); static class ExtensionMethods { // Pre C#14 syntax (introduced with C# 3) public static ReadOnlySpan<T> Truncate<T>(this ReadOnlySpan<T> span, int maxLength) { return span.Length <= maxLength ? span : span.Slice(0, maxLength); } // C# 14 syntax extension<T>(ReadOnlySpan<T> span) { public ReadOnlySpan<T> Truncate(int maxLength) { return span.Length <= maxLength ? span : span.Slice(0, maxLength); } } } |

A few remarks:

- If the extension is generic, the type parameter (if any) is specified immediately after the

extensionkeyword. - The receiver

ReadOnlySpan<T> spanapplies to one or more extension methods (or members) declared within the sameextensionblock. This logical grouping is a core advantage of the new syntax, improving clarity and structure when extending a type. - As far as the C# compiler is concerned, the two methods

Truncate()are strictly equivalent. Therefore, one must be commented out for the program to compile. - Notice the call to

AsSpan()in the first line. Extension methods require the receiver type to match exactlyReadOnlySpan<T>, hence it doesn’t apply tostringunless you explicitly cast. This is not specific to the new syntax but worth mentioning.

C# 14 Extension Everything

Extension everything embraces not only methods, but also extension properties and static extensions. I’ve always found the extra parentheses in calls like str.IsEmpty() a bit awkward for something that conceptually feels like a property.

Also extension operators have already been implemented and are expected to be available in .NET 10 Preview 7.

Here is a code sample demonstrating both extension properties and static extensions:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 |

const string longString = "this is a long string that needs to be truncated"; var span = longString.AsSpan().Truncate(20); Assert.AreEqual(span, "this is a long strin"); span = ReadOnlySpan<char>.TruncateStatic(longString, 20); Assert.AreEqual(span, "this is a long strin"); int x = span.LengthSquared; Assert.AreEqual(x, 400); string typeName = ReadOnlySpan<char>.GenericTypeParameterName; Assert.AreEqual(typeName, "Char"); static class ExtensionMethods { extension<T>(ReadOnlySpan<T> span) { // Instance extension method: can access 'this' span parameter public ReadOnlySpan<T> Truncate(int maxLength) { return span.Length <= maxLength ? span : span.Slice(0, maxLength); } // Static extension method: cannot access 'this' span parameter public static ReadOnlySpan<T> TruncateStatic(ReadOnlySpan<T> spanTmp, int maxLength) { return spanTmp.Length <= maxLength ? spanTmp : spanTmp.Slice(0, maxLength); } // Instance extension property public int LengthSquared => span.Length * span.Length; // Static extension property public static string GenericTypeParameterName => typeof(T).Name; } } |

Notice that extension properties are not necessarily read-only. A setter can also be declared:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 |

int[] array = { 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 }; var span = array.AsSpan(); span.LastItem = 10; Assert.AreEqual(array.LastItem, 10); static class ExtensionMethods { extension<T>(Span<T> span) { public T LastItem { get { return span[span.Length - 1]; } set { span[span.Length - 1] = value; } } } } |

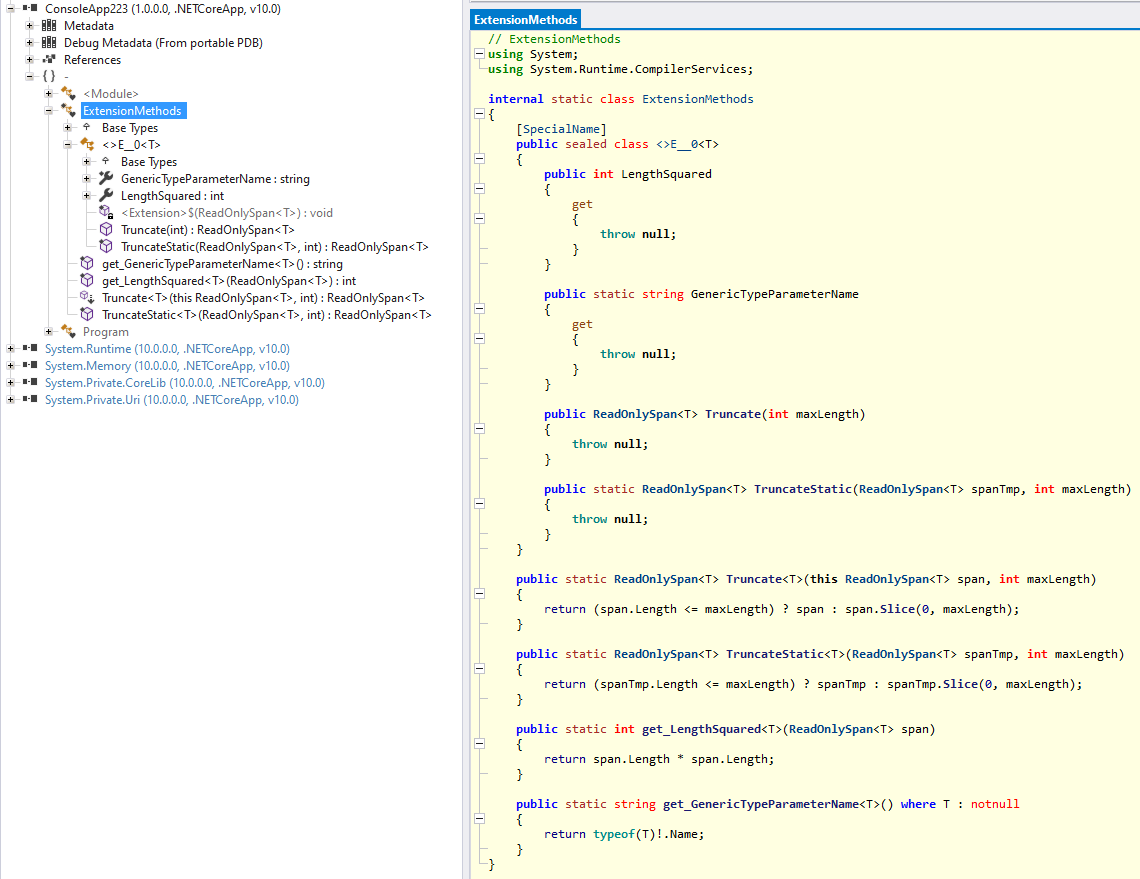

Decompiling Extension Everything

By decompiling the first program in the previous section with ILSpy, we can observe that a compiler-generated proxy class named <>E__0<T> is created. This class contains the extension members as if they were declared directly on the target type — exactly how we would like them to appear.

We can also see that extension properties are compiled as methods with name prefixed with get_. For anyone familiar with decompiling .NET code, this comes as no surprise — since the very beginning of C#, property getters have always been compiled this way. Also, property setters name are prefixed with set_.

Disambiguating extension members

Let’s address disambiguation. Until now, when multiple extension methods shared a similar signature, or hide an actual instance method, you had to disambiguate by explicitly prefixing the call with the name of the static class that defines the extension. This approach remains the standard way to resolve ambiguity and still applies to C# 14 extension members.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 |

var span = ExtensionMethods.Truncate(longString.AsSpan(), 20); // Disambiguate var span = longString.AsSpan().Truncate(20); span = ExtensionMethods.TruncateStatic(longString.AsSpan(), 20); // Disambiguate span = ReadOnlySpan<char>.TruncateStatic(longString, 20); int x = ExtensionMethods.get_LengthSquared(span); // Disambiguate int x = span.LengthSquared; string typeName = ExtensionMethods.get_GenericTypeParameterName<char>(); // Disambiguate string typeName = ReadOnlySpan<char>.GenericTypeParameterName; |

To the best of my knowledge, this is the first time the get_ or set_ property accessor prefixes appear explicitly in user-written C# code.

In the reddit link of the present article someone wrote: not sure why you still need the public static class to hold extensions now that there is a new extension block which could serve the same purpose. The answer is of course disambiguation. With no encapsulating named class, disambiguation is not possible.

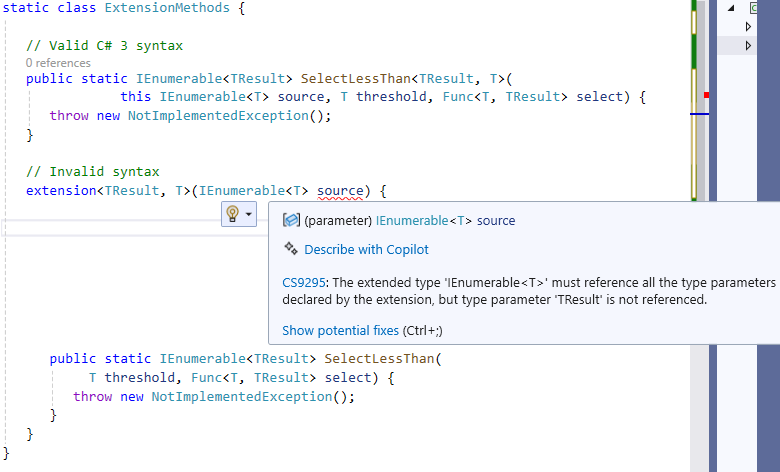

Some extension methods cannot be ported to the new C# 14 syntax

It’s worth noting that some complex extension methods cannot be ported to the new C# 14 syntax. The C# compiler requires all generic type parameters to be consumed in the receiver declaration. This is best illustrated in the following screenshot:

Also when a generic type parameter has some constraints, the extension method cannot be ported:

|

1 2 3 |

public static ReadOnlySpan<T> Truncate<T>(this ReadOnlySpan<T> span, int maxLength) where T : struct { return span.Length <= maxLength ? span : span.Slice(0, maxLength); } |

C# 14 and .NET 10 Preview

This article is based on C# 14 and .NET 10 Preview 6. If you’d like to try out extension everything before the official release in November 2025, you’ll need to use Visual Studio 2025 Preview, install the .NET 10 SDK, and update your .csproj file as follows:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

<Project Sdk="Microsoft.NET.Sdk"> <PropertyGroup> <OutputType>Exe</OutputType> <TargetFramework>net10.0</TargetFramework> <ImplicitUsings>enable</ImplicitUsings> <Nullable>enable</Nullable> <LangVersion>preview</LangVersion> </PropertyGroup> </Project> |

This article will be updated upon RTM release.

What about Extension Fields?

In the reddit link of the present article someone wrote: “One thing I believe this post doesn’t point out is that the new extensions still don’t support fields. This also means that an auto-property like string Status { get; set; } won’t work: that implicitly requires a backing field, which cannot be created.”

Extension fields are not supported and never will be. Instance extensions are simply convenient methods—or property accessors that compile down to methods—that operate on the public surface of an existing object. The underlying memory layout of values and referenced objects (which contain the fields) can only be expanded with new fields through inheritance.

Conclusion

Microsoft’s language designers have been thinking long and hard about how to extend extensions — literally. Managing all aspects—avoiding receiver repetition, handling disambiguation and generics, and ensuring no breaking changes—has been a challenging task.

With C# 14, we finally get a clean, unified and consistent syntax that brings some powerful benefits:

-

You can group related extension members by receiver type.

-

Extension properties are now supported.

-

You can even define static extension members.

-

Even more importantly, extension users never have to worry about how extensions are written. Whether using the old

this-parameter syntax or the new style, extensions should behave identically, ensuring existing methods keep working and users experience no disruption when authors update the syntax.